|

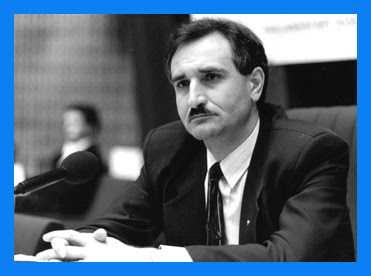

| По време на дебатите по приемането на България в Съвета на Европа - 5 май 1992г. |

|

| Председателстване на сесия на ПАСЕ |

Opinion 161 (1992)

Application by the Republic of Bulgaria for membership of the Council of Europe

Author(s): Parliamentary AssemblyOrigin - Assembly debate on 5 May 1992 (2nd Sitting) (seeDoc. 6591, report of the Political Affairs Committee, Rapporteur : Mr Martínez ;Doc. 6598, opinion of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights, Rapporteur : Mr Columberg ; and Doc. 6597Doc. 6597, opinion of the Committee on Relations with Non-Member Countries, Rapporteur : Mr Rathbone).

Text adopted by the Assembly on 5 May 1992 (2nd Sitting).

1. The Assembly has received from the

Committee of Ministers a request for an opinion on the accession of

Bulgaria to the Council of Europe (Doc.

6396), in pursuance of Statutory Resolution (51) 30 A adopted by

the Committee of Ministers on 3 May 1951.

2. It observes that democratic

parliamentary elections held by universal, free and secret ballot

were monitored by an ad hoc committee of the Assembly on 13 October

1991, when local elections, pronounced satisfactory by another

Council of Europe delegation, were also held.

3. The Assembly welcomes the European

commitment expressed before the Assembly by President Zhelev on 31

January 1991.

4. The Assembly appreciates the

contribution made by Bulgaria to the work of the Council of Europe,

both at parliamentary level since being granted special guest status

on 3 July 1990, and at intergovernmental level since acceding to

several European conventions, including the European Cultural

Convention, signed on 2 September 1991.

5. It attaches great importance to the

commitment expressed by the Bulgarian authorities to sign and ratify

in 1992 the European Convention on Human Rights and also to recognise

the right of individual application to the European Commission of

Human Rights (Article 25 of the Convention) as well as the compulsory

jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights (Article 46).

6. The Assembly considers that the

Republic of Bulgaria is able and willing :

6.1. to fulfil the provisions of

Article 3 of the Statute, which stipulates that ‘‘every member of

the Council of Europe must accept the principles of the rule of law

and of the enjoyment by all persons within its jurisdiction of human

rights and fundamental freedoms'' ;

6.2. to collaborate sincerely and

effectively in the realisation of the aim of the Council of Europe as

specified in Chapter I of the Statute of the Council of Europe

thereby fulfilling the conditions for accession to the Council of

Europe as laid down in Article 4 of the Statute.

7. The Assembly therefore recommends

that the Committee of Ministers, at its next meeting :

7.1. invite the Republic of Bulgaria to

become a member of the Council of Europe ;

7.2. allocate six seats to Bulgaria in

the Parliamentary Assembly.

1 April 1992

Doc. 6591

on the application of the Republic of Bulgaria

for membership of the Council of Europe

(Rapporteur: Mr MARTINEZ, Spain, Socialist) 1

SUMMARY

The report

examines political and institutional developments, resulting in

particular from the Bulgarian people's verdict of 13 October 1991,

from which a centre-right majority emerged for the first time since

the 2nd World War, in elections pronounced free and fair by an

all-party committee of parliamentary observers.

Special

attention is given to the system of guarantees for human and minority

rights by the report, which concludes that Bulgaria, a quarter of

whose population of 9 million consists of ethnic and religious

(predominantly Moslem) minorities, not only satisfies the conditions

for Council of Europe membership, but has a vital role to play in

bringing stability to the Balkan region.

I. DRAFT OPINION

1. The Assembly

has received from the Committee of Ministers a request for an opinion

on the accession of Bulgaria to the Council of Europe (Doc.

6396), in pursuance of Statutory Resolution (51) 30 A adopted by

the Committee of Ministers on 3 May 1951.

2. It observes

that democratic parliamentary elections held by universal, free and

secret ballot were monitored by an ad hoc committee of the Assembly

on 13 October 1991, when local elections, pronounced satisfactory by

another Council of Europe delegation, were also held.

3. The Assembly

welcomes the European commitment expressed before the Assembly by

President Zhelev on 31 January 1991.

4. The Assembly

appreciates the contribution made by Bulgaria to the work of the

Council of Europe, both at parliamentary level since being granted

special guest status on 3 July 1990, and at intergovernmental level

since acceding to several European conventions, including the

European Cultural Convention, signed on 2 September 1991.

5. It attaches

great importance to the commitment expressed by the Bulgarian

authorities to sign and ratify in 1992 the European Convention on

Human Rights and also to recognize the right of individual

application to the European Commission of Human Rights (Article 25 of

the Convention) as well as the compulsory jurisdiction of the

European Court of Human Rights (Article 46).

6. The Assembly

considers that the Republic of Bulgaria is able and willing:

i. to fulfil the

provisions of Article 3 of the Statute, which stipulates that "every

member of the Council of Europe must accept the principles of the

rule of law and of the enjoyment by all persons within its

jurisdiction of human rights and fundamental freedoms";

ii. to

collaborate sincerely and effectively in the realisation of the aim

of the Council of Europe as specified in Chapter I of the Statute of

the Council of Europe thereby fulfilling the conditions for accession

to the Council of Europe as laid down in Article 4 of the Statute.

7. The Assembly

therefore recommends that the Committee of Ministers, at its next

meeting:

i. invite the

Republic of Bulgaria to become a member of the Council

of Europe;

ii. allocate six

seats to Bulgaria in the Parliamentary Assembly.

II. EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM

by Mr Martinez, in cooperation with

MM Columberg and Rathbone

C O N T E N T S

Paragraphs

Introduction 1 -

2

I.

BACKGROUND 3 - 7

II. THE

INSTITUTIONS OF THE YOUNG DEMOCRACY

8 - 15

III. THE HUMAN

AND MINORITY RIGHTS AND THE RULE OF LAW

a. Freedom of

(bi-cultural) expression 16 - 18

b. The judiciary

and prison system 19 - 22

IV. BULGARIA AND

EUROPE 23 - 26

APPENDIX: Programme of the rapporteurs' visit

Introduction

1. Our joint

rapporteurs' fact-finding visit was greatly facilitated by the

Bulgarian National Assembly's all-party special guest delegation, and

its Secretariat, and by our ambassadors, of which those of

Switzerland, Ambassador Harald Borner, and of Spain, Ambassador

Joaquin Perez Gomez, continued the excellent tradition of support for

the Assembly's activities in non-member countries, among others by

the member country holding the Chairmanship of the Committee of

Ministers. Our warm thanks are due to Special guests and ambassadors

alike.

2. Our programme

(see Appendix) included talks with leading personalities in the

executive, legislative and judiciary, as well as with eminent

representatives of two important categories for a survey of the human

rights situation, namely newspaper editors and the prison service.

I. BACKGROUND

3. If, as has

been said, Bulgaria has tended to be forgotten by Europe, this is

because, during the cold-war era, rightly or wrongly, she presented

the image of an uniquely willing Soviet satellite, to the extent that

the possibility of full accession to the now defunct Union was

discussed. The Russians had after all twice come as liberators,

rather than oppressors: in 1878 after five centuries of Ottoman rule,

and in 1944 to expel the Nazis, even if murderous "communisation"

took place in the early post-war years. Later the respective leaders,

Brezhnev and Zhivkov, gave the impression of enjoying a prolonged, if

geriatric honeymoon, even if accompanied by the usual, and fateful,

establishment of massive economic dependence of Bulgaria on the

Soviet Union, also for energy supplies.

4. After being

long ignored, Bulgaria came most unfavourably to the notice of our

Assembly in 1985 (in the months following Mikhail Gorbachev's

assumption of leadership in Moscow) in connection with a crude

campaign of Bulgarisation directed mainly against the country's

ethnic Turkish minority. Thus

Resolution 846, adopted following debate on 26 September 1985 of

a report by the Committee on Relations with European Non-Member

Countries, called upon the then "People's Republic of Bulgaria

to put an end to the violation of the social, cultural and religious

rights of the minorities in question". It is likely that the

Zhivhov regime, disconcerted by the "new thinking" in

Moscow, was perversely seeking popularity with the Slav majority by

this campaign of blatant repression.

5. Throughout

the cold-war period "dissidence" was minimal in Bulgaria,

although today's Speaker of the National Assembly, Stefan Savov - who

received our delegation - was one of the brave representatives of an

intelligentsia who suffered prison while many others were simply

murdered during communisation.

(The historical background is comprehensively dealt

with in Mr Rathbone's supplementary report).

6. Later

Bulgaria obliged the world and European organisations in particular

to take highly positive note of her achievement in conducting,

observed by ad hoc observation delegations of our Assembly, free and

fair elections to a constituent Assembly on 10 and 17 June 1990 (see

Doc.

6279 Addendum) and to the National Assembly on 13 October 1991

(see Doc.

6543 Addendum). All three rapporteurs were involved in the

observation of one or the other election.

7. The last

elections indeed marked the loss of power by the (ex-Communist)

Socialist party and allies after 45 years, and was later (January of

this year) confirmed by the election, for the first time by direct

universal suffrage, of President Zhelyo Zhelev. In all cases there

was an impressively high, as well as peaceful, participation in the

vote - some 80 % - a figure whose attainment would be a rare event in

our member countries. Special guest status with our Assembly was

granted to the Bulgarian Assembly in July 1990.

II. THE

INSTITUTIONS OF THE YOUNG DEMOCRACY

8. The October

1991 elections brought about a peaceful transfer of power (without so

much as a "velvet" revolution) to the Union of Democratic

Forces (UDF), a coalition of Centre-Right parties (with 110 seats)

from the Socialist coalition (with 106 seats). Since the UDF is short

of an overall majority, an informal alliance exists with the Movement

for Rights and Freedoms (with 24 seats), a predominantly, but not

exclusively, Muslim and ethnic Turkish party, including also some

Slav muslims and non-muslims, including gypsies.

9. The new,

youthful and necessarily inexperienced government is only some

four months into its four-year term of office, and it was very

noticeable and not unnatural to our delegation that relations between

the majority and opposition are at present strongly confrontational,

a situation which also has its counterpart in some of our member

countries. Relations are particularly strained between the Socialist

party and MRF since each is seeking to outlaw the other. 53 members

of the Socialist party have introduced a petition to have the MRF

declared unconstitutional, whereas the latter is backing draft

anti-Socialist party legislation in parliament.

10. It is true

that the constitution (analysed by Mr Columberg in his opinion), in

Article 11.4, does not accept parties constitued on ethnic or

religious criteria. Such a principle - which is not accepted in the

majority of our countries - might have some justification as a

safeguard against fanaticism, but it should be interpreted with

flexibility, and certainly not at the expense of a reasonable party,

committed to the protection of minorities. This matter is currently

being considered by the Constitutional Court, whose President

Assen Manov received us. The Supreme Court had considered that the

MRF could participate in the October 1991 elections on the grounds

that it had been admitted to the 1990 elections. We gained the

impression that the Constitutional Court would deliver its verdict in

good time, but without undue haste. Your rapporteur was also

contacted by the member of the Court responsible for drafting its

ruling.

11. Our

delegation, without in any way wishing to interfere with a matter

that is sub judice, warned our Socialist 'Special guest'

friends of the danger of seeking to exclude and isolate a national

minority, which the sovereign people, in its wisdom, had voted to be

represented in its governing institutions.

12. The MRF, for

its part, retaliated by contesting the Socialists' right to exist,

and the UDF have drafted, and are threatening to introduce,

legislation aimed at "decommunisation" by banning former

communist holders of any paid office, which amounts to huge sectors

of the population, from the civil service and certain key economic

sectors, already the case for banking, for 5 years. Here again we

warned our special guest friends that ex-Communists, too, had a

"right to change" (or to conversion) which means that the

organs of the Strasbourg Human Rights Convention - which all parties

declare their readiness to accede to on joining our organisation -

would rule against collective punishments of the sort envisaged.

13. Time will no

doubt be needed for a political "middle-ground" to be

established, allowing consensus to replace confrontation. There

would, however, appear to be some urgency in view of the risk of

continued economic deterioration, characterised by high unemployment

and debt repayment, and falling productivity.

14. Our UDF

interlocutors insist that priority has indeed been given to economic

legislation (pointing to the foreign investment and banking and

credit laws). The next priority are the laws, of which 3 are already

adopted, on restitution of land and property to its pre-Communist

owners, as being the most effective approach to privatisation,

indispensable for a true change in the system. Only third priority is

given to introducting laws aimed at promoting "fairness"

which include declaring the sentences of the post-war "People's

courts" as nul and void. Also in this category fall the various

"decommunisation" drafts. The opposition, for its part,

accuse the government of giving first priority in reality to measures

of "reprisal", including "rehabilitation of fascists"

judged by the former People's courts, rather than to the necessary

structural improvement of the economy, which continues to deteriorate

bringing hardship to large sectors of the population, fearful of

change. They point out that the local elections on 13 October 1991

produced a majority of Socialist mayors in the countryside.

15. It is true

that the Constitution (see Mr Columberg's supplementary report) gives

mainly ceremonial powers to the President. Equally important,

however, is the political and moral legitimacy deriving from Zhelyo

Zhelev's (like his Vice-President, the poetess Blaga Dimitrova's)

direct election by the people. This cannot but strengthen their hand

in their ongoing dialogue with the government, party leaders and

foreign heads of state.

III. HUMAN

AND MINORITY RIGHTS AND THE RULE OF LAW

A. Freedom of

(bi-cultural) expression

16. The three

editors-in-chief we spoke to were as pluralistic - and as strongly

partisan - as the political parties to which they are closely linked:

Mr Kapsazov, recently appointed to edit Rights and Freedoms,

which publishes both a Bulgarian and a Turkish-language edition; Mr

Mutafov, the even more newly-appointed (one month ago) editor of the

still embryonic Democracy (an official organ of the UFD), and

Mr Stefan Prodev, the veteran editor of the former Communist party

organ, and now of the Socialist paper, Duma.

17. During our

exchange of views with a group of MRF representatives, led by our

special guest, Younal Lutfi, we learnt that the Movement feels that a

start has been made with the reversal of the crude "bulgarisation"

(including compulsory change of family names) of the mid-80s.

Moreover, today there is no problem with religious freedom (Mosques

are strongly in evidence as an element in Sofia's multicultural

heritage). But much, we were told, remains to be done in the field of

Turkish-language teaching and access to the state media. (No

privatisation has yet taken place in this area). It was striking how

high a proportion of TV and radio broadcasts are devoted to

parliamentary debates, a notable contribution to democratic

transparency and political education.

18. It was

hardly surprising that Duma , as the inheritor of the

infrastructures and professional expertise (including distribution

networks) of the former single-party regime, still has by far the

highest number of subscribers, at about 300,000, although this is

only one-third of the 1990 figure, "because of price rises",

we were told. In a confrontational political atmosphere, the editor's

belief that "press freedom is in danger", comes as no

surprise. He handed our delegation a letter, similar to one recently

addressed to President Mitterrand and others, in which he refers to

alleged government plans for "confiscate the property of public

organisations considered to have been part of the old system".

Such plans "if applied, would lead to the ridiculous situation

where the government would become the publisher of the main

opposition daily". Such intentions are denied by the government,

for example by Prime Minister Dimitrov in a letter to the London

Times of 19 March, which also contains a letter from Mr

Rathbone on the same subject.

b. The

judiciary and prison system

19. The

Bulgarian constitution (see Mr Columberg's report) guarantees the

separation of powers and the independence of the judiciary. For

obvious reasons, however, and for a transitional period, members of

the judiciary will continue to be those educated to a different

system, which does not mean that they should be denied the "basic

human right to change".

20. To meet the

special concerns of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights,

our delegation visited the Sofia Central prison, including the wing

reserved for frequent offenders, and those whose death sentences have

been, for the time being, suspended. Our delegation was accompanied

and briefed, not only by the Prison's Director, Mr Harizanov, but by

the Deputy Justice Minister, Mrs Koutzkova, and Mr Traikov, Director

of the Ministry's Penitentiary Service.

21. We found

conditions comparable to those in several of our member countries,

and a vigorously reformist attitude. This has already been actively

supported by the Council of Europe's Demosthenes Programme, which, in

May 1991, organised a European Expert Seminar in Sofia, and

subsequently arranged study visits for Bulgarian prison officers in

member countries (Austria, Denmark and the United Kingdom).

22. The

delegation found no reason, in the prison system or elsewhere, to

doubt that Bulgaria "accepts the principles of the rule of law

and of the enjoyment by all persons within its jurisdinction of human

rights and fundamental freedoms" (Article 3 of the Statute of

the Council of Europe).

IV. BULGARIA

AND EUROPE

23. Article 3 of

our Statute also provides that every member must "collaborate

sincerely and effectively" in the realisation of the aims of our

organisation. It was highly positive, in this connection, to learn

from the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Stoyan Ganev (on behalf of

Prime Minister Dimitrov, absent on a 10-day visit to the United

States) that, in spite of economic difficulties, his country has

every intention, once a member, of installing an Ambassador in

Strasbourg, so that he can act in the full sense as his country's

Permanent Representative.

24. This

assurance supplements the politically more significant assurance from

all political groups not only in favour of membership, but of, as far

as possible, simultaneous accession to, and rapid ratification of,

the European Convention on Human Rights, including the optional

declarations under Article 25 (individual petition) and Article 46

(compulsory jurisdiction of the Court), and to the Social Charter.

Also of great importance both for our organisation and for Bulgaria

would be the latter's full participation, with its highly relevant

experience, in our intense ongoing work on national minorities,

whether this finally takes the form of a separate Convention or an

additional protocol to the Human Rights Convention. We can be most

encouraged by the participation of the Bulgarian special guests since

the status was granted in July 1990, and by the government's

accession on 2 September 1991 to the European Cultural Convention,

which is no doubt the most important which non-member countries may

join.

25. The current

political controversy concerning the constitutionality of the

Movements for Rights and Freedoms must not disguise Bulgaria's truly

pioneering efforts in favour of multi-culturalism, of obvious special

application in the Balkans, where Bulgaria must be placed in a

position not only to constitute an almost miraculous "oasis of

peace", but an active factor of stability in the region.

26. As far as

Bulgaria's representation in the Parliamentary Assembly is concerned,

her population of 9 million, being more closely comparable to that of

Sweden (8.5 million) than any other member state, prompts the

delegation to propose six seats, like for Sweden.

APPENDIX

PROGRAMME OF THE VISIT OF THE RAPPORTEURS IN

SOFIA

FRIDAY 6 MARCH 1992

Dinner hosted by

the Spanish Ambassador,

H.E. Mr Joaquin

PEREZ GOMEZ

SATURDAY 7 MARCH 1992

Morning Talks

with

- Mr Alexander

YORDANOV and members of the Parliamentary Foreign Affairs Committee

- Members of the

Parliamentary group of the Union of

Democratic Forces (UDF)

- Members of the

Parliamentary group of the Coalition

of the Bulgarian Socialist party

- Members of the

Parliamentary group of the Movement

for Rights and Freedoms (MRF)

Lunch hosted by

Mr Stefan SAVOV, Speaker of the

National Assembly

Afernoon Talks

with

- Mr Assen

MANOV, President of the Constitutional Court

- Mr Stoyan

GANEV, Minister for Foreign Affairs

- Mrs KOUTZKOVA,

Deputy Minister of Justice,

- Mr TRAIKOV,

Head of penitentiary service, and

- Mr HARIZANOV,

Director of Sofia Central prison

Dinner hosted by

the Ambassador of Switzerland,

H.E. Mr Harald

BORNER

SUNDAY 8 MARCH

Dinner hosted by

Bulgarian Assembly's special guest

delegation to the Parliamentary Assembly

MONDAY 9 MARCH 1992

Morning Talks

with

- Mr Sliven

KAPSAZOV, Editor-in-Chief of

Rights and

Freedoms

- Mr Entcho

MUTAFOV, Editor-in-Chief of Democracy

- Mr Stefan

PRODEV, Editor-in-Chief of DUMA

Audition with Mr

Zhelyo ZHELEV, President of the

Republic

Press conference

TUESDAY 10 MARCH 1992

(Completion of

Mr Rathbone's programme)

Reporting committee: Political Affairs

Committee.

Committees for opinion: Committee on Legal

Affairs and Human Rights and Committee on Relations with European

Non-Member Countries.

Budgetary implications for the Assembly:

None.

Reference to committee: Doc.

6396 and Reference No. 1724 of 11 March 1991.

Draft opinion: Adopted by the committee with

18 votes in favour, none against and one abstention on 26 March 1992.

Members of the committee: MM Reddemann

(Chairman), Martinez, Sir Dudley Smith (Vice-Chairmen), MM

Alvares Cascos, Antretter, Mrs Baarveld-Schlaman,

MM Baumel, Björn Bjarnason, Caro, Cem, Cismozewicz,

Espersen, Fioret, Fiorini, Flückiger, Gabbuggiani, Ghalanos, Guizzi,

Mrs Halonen, MM Hardy, Hellström (Alternate:

Stig Gustafsson), Hyland, Irmer, Kelchtermans,

König, Mrs Lentz-Cornette, MM van der Linden,

Machete, Martins, Mimaroglu (Alternate: Güner), Miville,

Oehry, Pangalos, Papadogonas, Portelli, Schieder,

Sebej, Seeuws, Simko, Mrs Suchocka, MM Szent-Ivanyi, Tarschys,

Ternak, Thoresen, Ward.

NB. The names

of those members who took part in the vote are underlined.

Secretaries of the committee: MM Massie and

Kleijssen.

1

1 In co-operation with

Mr Dumeni Columberg (Switzerland, Christian Democrat), Rapporteur for

opinion of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights, and Mr

Tim Rathbone (United Kingdom, Conservative), Rapporteur for opinion

of the Committee on Relations with European Non-Member Countries.

16 April 1992

Doc. 6598

Doc. 6598

on the application of the Republic of Bulgaria

for membership of the Council of Europe 1

(Rapporteur: Mr COLUMBERG, Switzerland, Christian

Democrat)

1.

Introduction

The wave of

radical change in Central and Eastern Europe also affected Bulgaria.

Within a short time a break was made with the past and links with the

totalitarian régime were loosened. However, economic reform is a

more difficult, more painful process which takes far longer to

achieve than political change.

While the change

of régime in Czechoslovakia was called the Velvet Revolution,

Bulgaria can be said to have experienced a peaceful revolution, the

democratic process having been initiated "from the top down"

when the Bulgarian Communist Party (BCP) legalised political parties.

As in the

neighbouring countries, the first movements towards fundamental

reform began with the Gorbachev doctrine of glasnost and perestroika.

In Bulgaria itself the first tangible signs of reform appeared at the

Party Congress of 10 November 1989, when Todor Zhivkov was

ousted in a Politburo putsch led by Petar Mladenov and Dobri Djourov.

Legitimate aspirations to freedom, democracy and the rule of law

eventually led to the collapse of the Communist Party. The nature of

the process by which the old régime was overthrown meant that

specific problems also arose when change ensued.

1.1 The great

change

On 10 November

1989, President Todor Zhivkov was removed from power. At its XVth

Congress in March 1990, the BCP voted to become the Bulgarian

Socialist Party (BSP). When the first elections were held on 10 and

17 June 1990, the BSP obtained a majority, winning 52,75% of the

votes and 211 seats in parliament. The Union of Democratic Forces

(UDF) won 36% and 144 seats, the Agrarian Party 4% and 16 seats and

the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (MRF) 5,75% and 23 seats.

1.2

Application for accession (November 1989/February 1992)

Bulgaria

announced its intention to apply for Council of Europe membership on

3 March 1990. Following renewal of the application on 17 January

1991, the Committee of Ministers requested the Assembly's opinion on

12 February 1991.

1.3 Special

guest status

In September

1989 the Council of Europe created special guest status with the

Parliamentary Assembly with the aim of fostering and encouraging the

democratisation process in the countries of Central and Eastern

Europe. Bulgaria availed itself swiftly of this opportunity to

develop links with the Council of Europe and submitted its

application on 4 December 1989 with a view to setting up a framework

for co-operation as soon as possible.

The Bulgarian

Grand National Assembly was granted special guest status with the

Parliamentary Assembly on 3 July 1990. This enabled the Bulgarian

parliamentary delegation to co-operate with the Parliamentary

Assembly in its various fields of activity. These initial contacts

brought the two sides closer together and improved mutual

understanding.

Since then

numerous meetings have taken place between the Bulgarian Government

and parliament and the Council of Europe. They proved extremely

fruitful, as evidenced by the fact that Bulgaria has signed the

following conventions:

- European

Cultural Convention (2.9.1991)

- European

Convention on Information on Foreign Law (31.1.1991)

- European

Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage

(31.1.1991)

- Additional

Protocol to the European Convention on Information on Foreign Law

(31.1.1991)

- Convention on

the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats

(31.1.1991)

- Convention for

the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe (31.1.1991).

1.4 Our duty

to examine the application

The Committee on

Legal Affairs and Human Rights and the Committee on Relations with

European Non-Member Countries are both required to draft opinions on

the application, while the Political Affairs Committee is responsible

for examining the matter on its merits.

As with the

other membership applications upon which it was invited to comment,

the committee concentrated particularly on checking that the

following conditions had been satisfied: the holding of free

elections, the rule of law and observance of human rights as

guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights, backed up by

an intention to ratify the convention in the near future.

2.

Bulgaria's progression towards democracy

2.2

Background in brief

The country has

an area of 110 912 km2 and a population of 9 million,

including around 1 million inhabitants of Turkish origin. Its

territory is divided into 28 administrative units.

As a member of

the communist bloc from 1944 onwards, Bulgaria was one of the

countries which most closely followed Moscow's policy line - to such

an extent that it was sometimes called the 16th Soviet Republic.

The régime was exceptionally hardline and isolated from the rest of

Europe. Bulgaria's total dependence on the USSR was also reflected in

its economy. While over 80% of its trade was conducted with the

Soviet Union, the country had virtually no relations with Western

Europe. It is interesting to note that the Soviet Army was never

stationed on Bulgarian territory.

2.3 The first

signs of the great change

In the days

following 10 November 1989, a multiparty system was instituted, the

traditional parties were re-established, new parties emerged and an

opposition was formed. These developments were accompanied by the

restoration of freedom of expression. A national round table of

leading political figures was held at the start of 1990 and on 30

March 1990 fixed the date of the first free elections.

3. Free

elections

Delegations from

the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly were able to observe the

first elections in June 1990 followed by those on 13 October 1991.

The most important conclusions of these observer missions are

reproduced here.

3.1 The

elections on 10 and 17 June 1990

The "observer

missions" concluded that, in the circumstances, the conduct of

the elections was reasonably free and fair. Particular attention was

paid to the rights of the Turkish-speaking Muslim minority.

3.2 The

national elections on 13 October 1991

The second free

elections in Bulgaria were held on 13 October 1991 and were

observed by a delegation from our Assembly. They are described in an

information report by Mr Soares Costa (AS/Bur/Bulgaria (43) 3

rev.) which draws the following general conclusions: "The

Assembly delegation did not attempt to control the elections or make

a critical examination of the political situation. Given the size of

the delegation and the short time available, we were seeking to

arrive at a general political appreciation of the election process.

We did not comment on the application of Bulgaria to join the Council

of Europe even though certain points observed, for example the

banning of the formation of parties on ethnic or religious grounds

(Constitution 1991, Art. 11.4 and Electoral Law 1991,

Art. 41.4-3), clearly are relevant to this question. Our general

impression, as stated in the press communiqué, is that the Bulgarian

authorities had made a real effort to organise free and fair

elections. Partly because of this effort, but also as a result of the

compromises involved in adapting the electoral law and changes in the

structuring of the political forces, the resulting electoral system

was unnecessarily complicated and bureaucratic. Although

irregularities may have affected local results, we have no reason to

believe that significant fraud or malpractice took place to the

national benefit of any single party or coalition. We were, however,

unable to judge how free the electorate really was, in view of the

newness of the democratic tradition in Bulgaria".

Elections of

municipal councillors and mayors were held on the same day as the

National Assembly elections.

While the BSP

appears to be the strongest single party (the UDF is an alliance of

parties), it should perhaps be noted that the turnout of voters in

the Bulgarian elections (over 80%) was much higher than in other East

European countries.

By holding

these first free elections Bulgaria has fulfilled one of the

conditions for its accession to the Council of Europe.

3.3

Presidential elections in January 1992

Mr Zhelyu

Zhelev was elected President in July 1990 with the votes of the BSP.

Since his election, he has striven to overcome Bulgaria's isolation

and speeded up the process of democratisation. He visited the Council

of Europe and addressed the Parliamentary Assembly on 31 January

1991.

The first free

presidential elections were held in two rounds, on 12 and 19 January

1992. The outgoing President, Mr Zhelyu Zhelev, standing as the

UDF candidate, was elected in the second round with 52,85% of the

votes against 47,15% for Mr Velko Valkanov, an independent

candidate supported by the Socialist Party. The turnout was

approximately 76%.

4. Visit by

the committee of 19-21 December 1991 to Sofia, to the seat of the

parliament

The programme of

meetings and the list of discussion partners is appended.

The exchanges of

views with these representatives, whose competence and openness were

greatly appreciated, enabled the committee to obtain valuable

information and raise some critical questions.

During the

visit, the committee was able to hold talks with the Speaker of the

Bulgarian National Assembly, Mr Stefan Savov, the Vice-President and

members of the Assembly, including members of the opposition (that is

the BSP), the Chairman and Vice-Chairman of the Legislative

Committee, Mr Djerov; the Chairman of the Committee on Human Rights,

Mr Hodja; the Minister of Justice, Mr Loutchnikov; Minister of the

Interior, Mr Sokolov; Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr Dobrev;

members of the Constitutional Court, inter alia Professor Nenovski

and the Prime Minister, Mr Dimitrov.

The overall

impression gained was most positive. We were pleased to observe that

Bulgaria has made great progress in the process of democratisation

within an extremely short period of time. Our discussions showed that

Bulgaria's political leaders are firmly committed to continuing their

vigorous efforts to complete and consolidate the rule of law and

ensure observance of human rights. Both the government and parliament

are in favour of signing and respecting

international conventions such as the European

Convention on Human Rights.

The committee

paid particular attention to the conditions under which the National

Assembly's committees had been formed and how their chairmen had been

selected. Having been informed that the UDF was now challenging and

proposing to amend the Constitution which had been adopted by the

previous parliament without its support, the committee concentrated

on examining the text in order to see which provisions required

amendment in the opinion of the UDF. A number of suggestions which it

believes may be useful in this respect will be given in the

conclusions.

The committee

also attempted to determine whether the BSP would be prepared to

co-operate so as to permit the amendments necessary for early

ratification of the European Convention on Human Rights and

acceptance of its optional clauses.

Between 6 and

11 March 1992 the three Parliamentary Assembly Rapporteurs visited

Sofia. This visit provided a further opportunity for numerous and

fruitful discussions with representatives of parliament, the

government, political parties and the media. It enabled us to obtain

further information and to clarify any remaining questions. In

particular, the delegation held talks with:

- The President

of the Republic, Mr Zhelyu Zhelev;

- the Chairman

of the Foreign Policy Committee, Mr Alexander Zhordanov,

and members of the committee;

- the Speaker of

the Bulgarian National Assembly, Mr Stefan Savov;

- the Minister

of Foreign Affairs, Mr Stoyan Ganev;

- the

parliamentary group of the Union of Democratic Forces;

- the

parliamentary group of the Parliamentary Union for Social Democracy;

- the

parliamentary group of the Movement for Rights and Freedoms;

- the President

of the Constitutional Court, Mr Assen Manov;

- the Governor

of the central prison;

- the editors of

several journals ("Democracy", "Duma", "Rights

and Freedoms").

The results of

these discussions are set out in this report.

5. Some

important aspects of our examination

5.1 The

National Assembly

The Assembly

elected on 13 October 1991 is made up of 240 members

organised in three major political groupings: the largest, that is,

the UDF, has 110 seats, the BSP has 106 and the MRF (Movement for

Rights and Freedoms consisting chiefly of representatives of the

Turkish minority) has 24. Other political groups which presented

candidates failed to reach the threshold required for obtaining

seats. This means that approximately one-third of the electorate is

excluded from direct representation in the parliament.

There are 24

women in the Assembly, that is 10% of the total. The BSP was not

represented in the Assembly Bureau, at least until March 1992: it

refused the offer of one seat, claiming that its number of Assembly

members entitled it to two. It also challenges the legality of one of

the parties in the coalition, namely the MRF. However, it has been

established that the BSP is represented on all committees by a

delegation which reflects its true strength, although to date its

members have not headed any of the existing 18 committees (as

chairman or vice-chairman).

Recently,

however, a way out of the situation has materialised in the form of

co-operation on the leadership of the Committee on National Security

and Foreign Policy (vice-chairmanship). In spite of this, relations

between the "tenors" of the main three parties are tense,

as in the past. The three Rapporteurs were struck by the fact that

each group accuses the others of not being committed to democracy,

which bodes ill for close, constructive co-operation.

The Assembly's

powers are set out in Articles 84 to 87 of the Constitution. They

include legislative powers typically exercised by the parliaments of

our member states, namely the enactment of legislation and

ratification of international treaties, particularly those concerning

fundamental human rights.

Work

programme

The National

Assembly first had to finalise the electoral law for the presidential

elections. Its next priority is to implement the measures needed for

the transition to a market economy through small-scale privatisation,

the restitution of property and legislation on the economic

activities of non-residents.

The law on

reprivatisation, and in particular the draft Bill on banks and the

law on borrowing, have proved highly controversial in the past and

are continuing to do so. Provisions banning persons who collaborated

with the old régime from occupying leading positions in the banks or

in government for five years or more are coming in for particularly

heavy criticism. This condemnation of a whole category of persons is

problematic from the viewpoint of a state governed by the rule of law

and is contrary to international law. This is another reason why

Bulgaria should ratify the European Convention on Human Rights as

soon as possible: it would create the possibility of objective

supervision.

5.2 The

government

It should be

noted that the executive has no powers to dissolve the Assembly.

Nevertheless, the opposition party believes that the government has a

tendency to reduce the Assembly to a mere "rubber-stamp"

chamber.

Composition

and work programme

Mr Dimitrov

leads a minority government which depends on the support of the MRF.

Many of its Ministers have been chosen for their expertise. The

government has set itself the task of speeding up economic reforms

and developing international relations, particularly Bulgaria's

accession to the Council of Europe.

5.3 The

President of the Republic

The

President's powers

These are

defined in Chapter IV of the Constitution (Articles 91 to 104).

Article 92 states: "The President shall be the head of state. He

shall embody the unity of the nation and shall represent the state in

its international relations".

Article 93 sets

forth the procedure for election of the President and the length of

his term of office which may not exceed five years and can be renewed

only once.

The President's

powers are limited and he has little influence over parliament. The

President has a relative right of veto, is not entitled to propose

bills or reject those which have already been debated but merely

return them for further debate.

Recently

constitutional conflicts have arisen between the President of the

Republic and the parliament. In view of the fact that the President

is elected by the people, he enjoys a degree of legitimacy.

Nevertheless, this is currently a source of conflict.

The President works with his own staff and assumes

particular responsibility for foreign policy and defence.

5.4 The

Constitutional Court

Composition

The provisions

concerning the Constitutional Court are set forth in Articles 147 to

152 of the Constitution. Article 147 reads as follows;

"1. The Constitutional Court shall consist of

12 justices, one-third of whom shall be elected by the National

Assembly, one-third shall be appointed by the President [of the

Republic], and one-third shall be elected by a joint meeting of the

justices of the Supreme Court of Cassation and the Supreme

Administrative Court.

2. The justices of the Constitutional Court shall be

elected or appointed for a period of nine years and shall not be

eligible for re-election or re-appointment. The make-up of the

Constitutional Court shall be renewed every three years from each

quota, in a rotation order established by a law.

3. The justices of the Constitutional Court shall be

lawyers of high professional and moral integrity and with at least

fifteen years of professional experience.

4. The justices of the Constitutional Court shall

elect by secret ballot a Chairman of the Court for a period of three

years.

5. The status of a justice of the Constitutional

Court shall be incompatible with a representative mandate, or any

state or public post, or membership in a political party or trade

union, or with the practising of a free, commercial, or any other

paid occupation.

6. A justice of the Constitutional Court shall enjoy

the same immunity as a member of the National Assembly."

Four of the

current justices were appointed by the Grand National Assembly formed

as a result of the elections of June 1990, in which the communists

had a majority. But it should be noted that the number of votes

gained by the BSP was greater than the number of justices allocated

to this party.

According to

information received from the President of the Constitutional Court,

prior to the elections six justices belonged to the BSP and one to

the Social Democratic Party. After the elections they all handed in

their party cards.

Justices who

fail to carry out their duties or suffer incapacitation may be

removed from their post before the end of their term of office by the

group which appointed them.

Every three

years one third of the justices of the Constitutional Court must be

replaced, that is, two from the group of justices appointed by the

President of the Republic and one from each group appointed by the

other elected bodies. The outgoing justice is selected by the drawing

of lots.

The committee

believes that former membership of the Communist Party should not

automatically be taken as sufficient reason for disqualification

given that party membership was an essential precondition for the

holding of certain posts, particularly in higher education.

It is more

appropriate to judge by the guarantees given today and to accord them

due credit. Although the judges were trained under the former

communist regime, it should be noted that Bulgaria prided itself on

having a legal system comparable to those of other European countries

before the second world war and that Bulgarian intellectuals

maintained links with the West and Western culture even during the

communist period.

Functions

Article 149

states:

"1. The

Constitutional Court shall:

1.

provide binding interpretations of the Constitution;

2. rule on challenges to the constitutionality of the laws and other acts passed by the National Assembly and the acts of the President;

3. rule on competence suits between the National Assembly, the President and the Council of Ministers, and between the bodies of local self-government and the central executive branch of government;

4. rule on the compatibility between the Constitution and the international instruments concluded by the Republic of Bulgaria prior to their ratification, and on the compatibility of domestic laws with the universally recognized norms of international law and the international instruments to which Bulgaria is a party;

5. rule on challenges to the constitutionality of political parties and associations;

6. rule on challenges to the legality of the election of the President and Vice-President;

7. rule on challenges to the legality of an election of a Member of the National Assembly;

8. rule on impeachments by the National Assembly against the President or Vice-President.

2. No authority

of the Constitutional Court shall be vested or suspended by a law".

The

Constitutional Court thus has an extremely important function since

it is required by Article 149(1).4 to rule on the compatibility

between the Constitution and the international instruments concluded

by the Republic of Bulgaria prior to their ratification, and on the

compatibility of domestic laws with the universally recognised norms

of international law and the international instruments to which

Bulgaria is a party. There has been some criticism of the fact that

individuals cannot bring cases directly before the Court, but the

same applies in several member states.

The Court is

currently considering the case of the BSP's challenge to the legality

of the MRF. The stability of the current system will depend on its

ruling since annulment of the MRF would lead to the dissolution of

the Assembly and provoke extremely grave reactions from the Turkish

minority which forms the party's major support base.

In this respect,

the Court representative whom the committee met stressed that the

Court would seek a solution that would not stir up tensions and would

not lead to violations of human rights. According to President Assen

Manov, a decision should be taken in April or May 1992.

The composition

of the Constitutional Court gave rise to some extremely critical

debate in the committee. Although we still have some reservations on

the matter, we hope that the Court is aware of the great

responsibility it holds and that it will prove equal to the task.

5.5 The

Constitution of the Republic of Bulgaria, adopted by the Grand

National Assembly on 12 July 1991

We have already

indicated that the party now in power, the UDF, has criticised the

Constitution which it did not vote for and wishes to see amended as

soon as possible even though this does not seem feasible in the

current Assembly.

When asked which

articles they wished to have amended, the party's representatives

gave no precise indications but stated that they numbered some 40 in

all.

For its part,

the committee conducted a critical examination of the Constitution

and reached the conclusion that it does not, in general, merit severe

criticism. Indeed, its contents were inspired by the constitutions of

several of our member states. The committee nevertheless found some

articles which should either be modified to comply with the European

Convention on Human Rights or interpreted by the Constitutional Court

in a manner compatible with the convention.

In our opinion,

the most controversial articles are the following:

Article 11.4: "There shall be no political parties on ethnic, racial or religious lines, nor parties which seek the violent usurpation of state power.

Article 12.2: "Citizens' associations, including the trade unions, shall not pursue any political objectives, nor shall they engage in any political activity which is in the domain of the political parties".

Article 13:

"1. The practising of any religion shall be free.

2. The religious institutions shall be separate from the state.

3. Eastern Orthodox Christianity shall be considered the traditional religion in the Republic of Bulgaria.

Article 36:

1. The study and use of the Bulgarian language shall be a right and an obligation of every Bulgarian citizen.

2. Citizens whose mother tongue is not Bulgarian shall have the right to study and use their own language alongside the compulsory study of the Bulgarian language.

3. The situations in which only the official language shall be used shall be established by a law".

Article 44:

1. "Citizens shall be free to associate.

2. No organisation shall act to the detriment of the country's sovereignty and national integrity, or the unity of the nation, nor shall it incite racial, national, ethnic or religious enmity or an encroachment on the rights and freedoms of citizens; no organisation shall establish clandestine or paramilitary structures or shall seek to attain its aims through violence.

3. The law shall establish which organisations shall be subject to registration, the procedure for their termination, and their relationships with the state".

A few critical observations; the situation of the majority

One of the

problems raised by the UDF is that of amendments to the Constitution;

Article 155 states that constitutional amendments require a

majority of three-fourths of the votes. At the second reading, a

majority of two-thirds is required. The BSP would therefore

have to support the amendments to allow their adoption.

The question of

the death penalty was also raised. Although it still exists

and 17 death sentences have been delivered over the last two years,

it is no longer applied. This is a situation which many of our member

states experienced when they were already parties to the European

Convention on Human Rights. Asked about the government's intentions

on the matter, the Minister of Justice pointed out that it would be

extremely difficult to abolish the death penalty entirely at the

present juncture since 80% of the population believed it should be

maintained.

5.6 Ethnic

groups

Difficult

relations with the different ethnic groups gave rise to tremendous

problems and political tensions. The natural integration process was

accelerated by draconian administrative measures. For example, at the

end of 1984 Turks resident in Bulgaria were forbidden to use their

Turkish names. This was a serious mistake which triggered mass

emigration by the Muslim community (300 000 people) and a sharp

deterioration in relations with Turkey. The situation did not

fundamentally improve until the decree of the Council of State and

the Council of Ministers of the People's Republic of Bulgaria of 29

December 1989 guaranteeing citizens' constitutional rights came into

force. Since then approximately 130 000 émigrés have returned to

Bulgaria, and according to an official of the MRF the question of the

restitution of property should be resolved in a satisfactory manner.

The Constitution

does not guarantee the rights of minorities. We have just seen that

it includes a number of provisions which limit their rights (Art.

11.4). However, the law has since been repealed.

Following his

visit to Sofia, the Rapporteur learnt that there is now provision for

four hours a week of Turkish language teaching. This appears to

provide an acceptable solution for those concerned. Since the

beginning of 1991, the MRF has published a newspaper in Turkish.

Gipsies

were said to make up a particularly high percentage of the criminal

population and also to receive the most severe sentences.

As our hosts

affirmed, the best way towards integration and harmony between

communities is to involve the Turkish population in the business of

governing. For this reason the present government welcomes

participation by this ethnic group in parliament and at local and

regional level. This presence has already made an enormous

contribution to calming the situation.

5.7 Priority

to international agreements, in particular the European Convention on

Human Rights

Article 5.4 of

the Constitution stipulates: "Any international instruments

which have been ratified by the constitutionally established

procedure, promulgated and come into force with respect to the

Republic of Bulgaria, shall be considered part of the domestic

legislation of the country. They shall supersede any domestic

legislation stipulating otherwise".

The

Constitutional Court will therefore be called upon to rule on the

compatibility between the Constitution and the European Convention on

Human Rights prior to its ratification. Its interpretation of the

Constitution will permit clarification of a number of points which

might pose problems.

5.8

Legislative reform

The parliament

is currently working on a vast programme of legislative reform.

Between the last elections (13 October 1991) and the beginning of

March 1992 it adopted more than 30 new laws. A number of laws, such

as the laws on reprivatisation and agricultural reform, concern the

economy.

However,

difficulties have arisen from the fact that the communist-dominated

administration is continuing to put a brake on reforms and that the

"decommunisation" process and the abolition of the old

régime are taking time. All Communist Party property not acquired

prior to 1946 or after the reform has been confiscated.

The issue of

whether individuals who held important Communist Party posts should

be allowed to resume leading positions in state bodies and banks is

currently being discussed. The dismantling of the communist régime

is designed to prevent the main beneficiaries of the old system from

transferring state property abroad or to private companies and thus

retaining their privileged positions. There is a likelihood of this

since the individuals concerned are often well-qualified. It should

also be seen as an inevitable reaction to years of oppression under

communist rule.

The BSP and

other representatives object on the grounds that a collective

sanction of this type would be unacceptable and would lead to new

injustices. It would be contrary to the principles of established law

and would certainly not be endorsed by the European Court of Human

Rights. For this reason the socialists are highly interested in

co-operation with the Council of Europe; they hope that their demands

and rights will be upheld in Strasbourg.

Apparently 200

diplomats who worked for the secret service have recently been

dismissed.

Generally

speaking, relations between the party leaders are extremely tense.

The present violent disputes are probably due to decades of enforced

"calm". There is evidence of intolerance (eg the BSP's

demand that the MRF be banned). Each group accuses its rivals of not

understanding democracy.

5.9 The

economic situation

A 20% fall in

production and unemployment of 400 000 were expected for 1991.

The economic

situation is still difficult (problems related to the foreign debt

and agricultural production). The foreign debt amounts to

approximately USD 12 thousand million. Almost 40% of the 4,3 million

workers, including 2 million pensioners, are living on the poverty

threshold. Even though the impression is that the crisis is worse

than ever, food supplies were noticeably better this winter (1991/92)

than last year. Inflation has been pushed down by 7-8%. Prices have

been liberalised. But the transition to a market economy is by no

means easy and many problems remain.

Nevertheless, a

remarkable spirit of enterprise can be observed in the retail sector.

Small stalls are being set up everywhere, reflecting an upturn in

economic activity.

However, major

problems remain in industry. The situation has been worsened by

tremendous energy-related problems (falling oil exports from the

former USSR and recurring difficulties with the Kosloduj nuclear

power station).

5.10 The

media

There are no

restrictions whatsoever on press freedom and each political party has

its own newspaper.

6.

Conclusions

The Committee on

Legal Affairs and Human Rights has examined in detail those aspects

of Bulgaria's situation which determine whether or not it may accede

to the Council of Europe, namely the functioning of parliamentary

democracy, the rule of law and human rights. It noted that Bulgaria

has made considerable progress in the process of democratisation and

that the authorities at present in office intend to continue

democratic reforms. It particularly welcomed the fact that the

present constitution specifically recognises the pre-eminence of

international law. The fact that the authorities intend to sign a

number of international conventions, including the European

Convention on Human Rights, affords a guarantee of the observance of

human rights according to international standards in Bulgaria. In

examining the application, the Legal Affairs Committee found a number

of shortcomings, for instance in the field of constitutional law. It

expects the government and parliament to put these right within a

short time. Article 5, para. 4, of the Constitution affords the

means of enforcing the rule of law by giving international law

precedence over contradictory provisions of domestic legislation.

The Committee on

Legal Affairs and Human Rights can, in conclusion, confirm that it

has seen plentiful evidence that Bulgaria gives cause for

satisfaction in this respect and that this new democratic state

fulfils the conditions required to become a member of the Council of

Europe and a party to the European Convention on Human Rights.

The Constitution

ought, however, to afford greater protection of certain rights and

freedoms.

The Bulgarian

authorities have expressed an urgent desire to accede to the Council

of Europe as soon as possible and join the community of European

nations.

The government

has confirmed its intention to sign the European Convention on Human

Rights and the opposition party has indicated it would react

positively to this.

Political

pluralism is guaranteed and all institutions are elected by universal

suffrage.

All the

conditions required for membership of the Council of Europe have

therefore been met. Consequently, we support Bulgaria's application

and welcome its return to the European fold. Membership of the

Council of Europe will help to consolidate this new democracy and

will require the introduc11tion of a market economy in Bulgaria,

which is in the interest of Europe as a whole. We all benefit from

this development, because a continent which has open borders and is

divided between a rich half and a poor half will not be stable in the

long term. Finally, harmonious neighbourly relations can only be

achieved between states which subscribe to the same

ideals.

The transition

from a totalitarian state to a democratic system is fraught with

difficulties, as we have seen elsewhere. It requires time and

patience. Attitudes do not change overnight. Changing the structures

of the state, society and the economy is also extremely difficult.

Nevertheless, we must be optimistic and have faith in the new

leaders. Membership of the European family also provides new

opportunities for the observance of human rights and for the rapid

introduction of the rule of law.

A P P E N D I X I

LIST OF BULGARIAN PERSONALITIES

MET DURING THE MEETING IN SOFIA

19-20 December 1991

(in chronological order)

Mr SAVOV,

Speaker of the National Assembly (UDF)

Mrs

BOTOUCHAROVA, Vice-President of

the National Assembly (UDF)

Mr KADIR,

Vice-President of the National Assembly

Mr DJEROV,

President of the Legislative Committee

Mr HODJA,

President of the Committee on Human

Rights

Mr

LOUTCHNIKOV, Minister of Justice

Mr

SOKOLOV, Minister of the Interior

Mr DOBREV,

Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs

Prof.

NENOVSKI, Member of the

Constitutional Court

Mrs

ANANIEVA, President of the

Parliamentary Union for

Social Democracy

Mr

VIDENOV, President of the

Socialist Party

Mr BOKOV,

Spokesman for foreign affairs of the

Socialist Party

Mr

DIMITROV, Prime Minister

A P P E N D I X II

PROGRAMME

of the meeting held from 19 to 21 December 1991

in Sofia

at the seat of the parliament (East Room)

Thursday 19 December 1991

9.45 am

Departure on foot from Hotel SOFIA (tel. 3592878821) to

the parliament

10.00 am

Working session

- statement by Mr Stefan Savov, Speaker of the National Assembly

- exchange of views with members of the Bureau of the National Assembly

11.00

am Exchange of views with the

President of the Legislative

Committee

12.00 am

Exchange of views with the President and members of the

Committee on Human Rights

1.00 pm Lunch

not hosted

3.00 pm

Working session

Exchange of views with Mr Svetoslav Loutchnikov, Minister of Justice

4.00

pm Exchange of views with Mr

Yordan Sokolov, Minister of the

Interior

5.00 pm Exchange

of views with the Vice-Minister for Foreign Affairs

8.00 pm

Reception hosted by the Speaker of the National Assembly

Mr Stefan Savov

Friday

20 December 1991

9.15 am

Departure on foot from Hotel SOFIA to the parliament

9.30 am

Working session of the committee

11.00 am

Exchanges of views with Prof. Nenovski, member of the

Constitutional Court

12.00 am Meeting

with the Prime Minister, Mr Dimitrov

1.00 pm Lunch

not hosted

2.30 pm Press

conference

3.30 pm

Working session of the committee

8.00 pm

Dinner hosted by the Bulgarian delegation with

special guest status with the Council of Europe

Saturday

21 December 1991: Excursion

8.30 am

Departure for the monastery of Rila

10.00 am Visit

of the monastery

12.00 am

Departure for Blagoevgrad

1.00 pm Lunch

hosted by the Mayor of Blagoevgrad

2.30 pm Visit of

the town

3.30 pm

Departure for Sofia

5.00 pm Arrival

in Sofia: free evening

Sunday, 22 December 1991

Departure of members of the committee

Reporting committee: Political Affairs

Committee

Committees for opinion : Committee on Legal

Affairs and Human Rights and Committee on Relations with European

Non-Member Countries

Reference to committee: Doc.

6396 and Reference No. 1724 of 11 March 1991

Opinion: Approved by the committee on 13

April 1992.

4 May 1992

Doc. 6597

Doc. 6597

O P I N I O N

on the application of the Republic of Bulgaria

for membership

of the Council of Europe 1

(Rapporteur: Mr RATHBONE, United Kingdom,

Conservative)

General Background

1. Until late

1989 Bulgaria was dominated by the Communist Party. But the

superficial picture of relatively stable politics and economic

prosperity had begun to crack long before then. Bulgaria's alleged

involvement in the death of Georgi Markov in 1978 and in the

attempted assassination of the Pope in 1981, its support for

terrorism and drug trafficking, the pervasive corruption and

nepotism, and its human rights abuses had severely damaged its

international reputation.

2. Meanwhile,

changes in the Soviet Union and throughout Eastern Europe were making

President Zhivkov and his policies more and more of an anachronism,

especially in the eyes of President Gorbachov. The catalyst for

change was provided during a CSCE-sponsored Environmental Conference

in Sofia in October 1989, when police beat up members of a small

environmental pressure group, Ecoglasnost, in front of members of the

international press and the diplomatic community. Zhivkov was removed

in a palace coup on 10 November 1989.

3. Over the

following year the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) (that is the

renamed Communists) was gradually eased out of its positions of

power. After the first reasonably free and fair elections in June

1990, the Presidency went to Dr Zhelev, leader of the UDF, a

non-Communist umbrella grouping. Although the BSP held on to the

government for a further five months they failed to establish their

authority, and collapsed on 29 November in the face of a wave of

student and labour unrest. Subsequently, after much political

in-fighting, a politically independent lawyer, Mr Dimitur Popov,

formed a coalition government in December, embracing members of the

BSP, UDF, the Agrarian Union (a peasant party), and independents;

this was the first genuinely multi-party government in Bulgarian post

war history. Seven government posts went to the BSP, four to the UDF,

three to the Bulgarian Agrarian Party and five to the Independents.

Dimitur Popov was selected to be a non-party Prime Minister.

4. In January

1991 all the major political parties agreed on a programme of

substantial economic and constitutional reform.

Bulgarian Parliament

5. The Bulgarian

Parliament consists of a single chamber (the National Assembly) of

240 members elected for a 4-year term.

Constitution

6. A new

constitution was adopted by the Grand National Assembly on 12 July

1991, with the BSP using its majority to secure acceptance. Much

stress is laid in the new constitution on the role of the new

Constitutional Court (which has the power to rule on the

constitutionality of legislation passed by the National Assembly) and

the independence of the Judiciary.

7. Though the

constitution marks a considerable advance on the previous one, it

attracted some criticism, especially from the radical right wing of

the UDF. The UDF objected that the constitution was a "communist"

one which depended for its passage through parliament on the votes of

the majority BSP. Others argue that the constitution was ill-suited

to modern requirements because it reflected an outdated,

paternalistic type of state; that excessive power was vested in

parliament while the powers of the President were considerably

restricted; and that the constitution ignored the natural rights of

the individual and took into account only those rights which the

state grants to the individual.

8. In the light

of various investigations into minority rights in Bulgaria by the

Council of Europe over recent years (Resolution 846 in 1985, on the

situation of ethnic and Moslem minorities in Bulgaria;

Recommendation 1109 in 1989 on refugees of Bulgarian nationality

in Turkey;

Resolution 927 in 1989 on the situation of the ethnic and Moslem

minority in Bulgaria), it will not be surprising for members of the

Assembly that the absence of more positive provisions for collective

minority rights and the continuing ban on religious and ethnically

based parties (which later threatened to disenfranchise the mainly

ethnic Turkish Movement for Rights and Freedoms) have also given

cause for concern.

Parliamentary elections

9. A new

Electoral Law was passed on 22 August 1991 establishing a system of

proportional representation for parliamentary elections. In September

the MRF contested the legally questionable objection to its

registration as a party. Council of Europe Ministers raised this with

Bulgarian political leaders and authorities, and subsequently the MRF

were allowed to participate in the elections held on 13 October 1991.

10. The

Bulgarian National Assembly, Government and Central Electoral

Commission invited international observers from the Council of Europe

and other national and international bodies. Your rapporteur was a

member of our Assembly's Ad Hoc Committee. The full report is

published in Doc.

6543 Addendum I. In common with other observer bodies, we

concluded in summary that:

- the elections

were broadly free and fair, more so than the June 1990 elections,

which themselves were largely accepted by both the Bulgarian people

and the international community.

- the elections

were impressively organised. Their complexity was formidable, since

they consisted of four simultaneous polls: national, local, council

and mayor. Potential for confusion was great, but in the event

observer teams found remarkably little.

- there was no

violence.

11. Following

the elections, the Union of Democratic Forces became the largest

single party with 34.4% of the vote (110 seats). The Bulgarian

Socialist Party gained 33.1% (106 seats). The Movement for Rights and

Freedoms won 7% of the vote (24 seats). Other parties failed to clear

the 4% threshold to win seats. The turnout was 83.87%.

12. The

Bulgarian Parliament held its first post-election meeting on 4

November and Philip Dimitrov formed the new UDF Government on

8 November. This did not include ministerial posts

for MRF members, but the Government depends in parliament on MRF

support.

Presidential elections

13. Bulgaria's

first-ever democratic elections for a directly-elected President and

Vice-President took place in two rounds on 12 and 19 January 1992.

The nominees of the ruling UDF party, the incumbent President Zhelyu

Zhelev and his running mate, Mrs Blaga Dimitrova (poet and UDF MP)

won - after being forced into a second round - with 53% of the vote.

Turnout was around 76%.

The Constitutional Court

14. As provided

in the Constitution, this Court was established in September 1991. It

is composed of 12 members, one-third elected by the National

Assembly, one-third elected by the Judges of the Supreme Courts and

one-third appointed by the President of the Republic. There have been

some questions raised about membership of the Court, specifically due

to some links to the previous communist regime. But by history and by

clearly-stated intent, Bulgaria's commitment to an independent

judiciary of the highest professional and moral integrity should mean

that the Constitutional Court will operate as it should as the

interpreter of the Constitution and the defender of proper

constitutional practice.

15. The

Constitutional Court has an extremely important role in interpreting

the constitutionality of laws and ruling on the compatibility between

the Constitution and international legal instruments such as the

European Convention on Human Rights. Reassurances have been given

that the Court would uphold the Convention's supremacy over the

Constitution should one be found at variance with the other, at time

of ratification.

16. This is

specially important in the light of the Court's present consideration

of the legality of the MRF, accused of being a mainly ethnic Turkish

movement by the BSP, the previous Communist party. This is based on

Article 11.4 of the Constitution: "There shall be no political

parties on ethnic, racial or religious lines, nor parties which seek

the violent usurpation of state power" - unique in Europe, and